I wiped off the last bits of shaving cream with a towel and inspected the edges of my face to make sure I hadn’t missed a spot. Then I came out to the dining table to show the girls my new face. When I emerged, Juni was standing on her chair midway through her sermon about chips (she believed the right time to open them was five minutes into our 8-hour drive). Runi was tracing clouds through the dal on her plate, while Alka, their nanny, begged her to take a bite.

They smiled and cheered when they heard my door open. They had been excited about the full shave for weeks and their applause came before they took a good look. Then they did. The cheering stopped. Their faces went blank.

“Toh? Kaisa hai? Do you like it?”

I turned my face one way, then the other. I stuck my chin out and looked up to stretch my neck. I pulled my lips down to reveal the strip below my nose.

Their eyes searched for something familiar. Some shading, contrast, a distinction between face and neck. But they did not find it. All they saw was a strange man.

Runi pulled Alka in front of her as a shield. She watched me through the little crack under Alka’s armpit and when she just could not recognize me, snarled like an angry cat. Juni put her thumb in her mouth and froze where she was standing, looking confused but considerably less repulsed than her sister.

All Runi needed, I gathered, was to witness Juni be normal. If Juni gave me a hug or a high-five, her sister would be okay. I walked towards Juni, but one step was as far as I got before fat tears rolled down her face. I hugged her instinctively and she punched my chest to get away. I backed off.

They both now hid behind Alka, wailing, while she tried to convince them, over and over again, that it was me. “Ye Papa hain. Arey ye PAPA hain.” Clean-shaven Papa, alien Papa, ugly Papa maybe, but Papa nonetheless. They knew Papa though, and no, this was not him. I reasoned, tried to sing a song, cracked a bad joke. The wailing grew louder.

It’s upsetting to see your children wince at the sight of your face, but someone once said that the key to a healthy parent-child relationship is a high tolerance for rejection. I get plenty of practice.

Our bags had been packed for hours. The car was already loaded. Dinner was running only slightly late. It is rare to see this kind of efficiency from me the night before a 6am departure. Especially if Tara is out of town. June is the one time she gets a break from work, and I had forced her to visit her sister in London. I’d assured her the four of us would be fine: the girls, Alka, and I. Go have fun, I had said, I’ll manage.

But our 6am start was now looking ambitious.

“WAIT”, I yelled, and ran into their room. I opened the top-drawer of their shelf which stores every object in the universe. I rummaged through batteries, Lego pieces, old spectacles, a single airpod, a thermometer, before I found a black sketch pen. I roughly dotted a moustache and stubble on my face, as the crying reached a crescendo - and ran back out. “SEE!!!”

The crying stopped. The look of confusion did not disappear, but changed colour. I had walked into their room a stranger and walked out as me. A mean magic trick. Juni loosened her lips around her thumb and took a deep breath. Runi peaked out from behind Alka and said, “Hi Papa!”.

The first step of my weekly personal grooming ritual is to draw a line across my cheek with shaving cream. A border that separates trimmer territory from razor territory. The trimmer is used to shape the fuzz I like to call my ‘stubble’. It does all the heavy lifting. The role of the razor, on the other hand, is limited: clean up the mess around the fuzz but do not breach the border.

When the kids hear the buzz of my trimmer in the bathroom, they bang on the door till I open. I make some space on the counter. They watch transfixed as the contours become clearer, dark patches get lighter, neater, and my face finds more definition. Each time they watch me tiptoe around the fuzz with my razor, they try to change my mind: “Papa full shave karo”.

But I know better.

That fuzz is the keeper of my jawline. It serves as a cage and keeps my skin from oozing all over the place like a Dali clock. Stripping my face clean changes its shape from triangular, to square with round edges. When I do this - once in three or four years - my phone disobeys all facial commands and asks for a passcode.

The last time I was clean-shaven was before the kids came home. They had never seen me without the fuzz. But I wasn’t shaving only for the sake of their curiosity. My chin had stopped sprouting hairs so much as multiple yellowish-green strands of different shapes, all emerging from the same root. It was time for a fresh start.

The first couple of hours of our road trips are always the best kind of chaotic. Runi wants to start with music, Juni with a round of ek macchli. Runi jumps between seats to find the one with the best view, Juni lectures her on the essential safety function of seatbelts. Uttarakhand is closer than Gurgaon, they believe, and fail to understand what could possibly take us so long.

But on this bright and lovely morning, they are silent. My makeshift beard from the night before has disappeared, and they don’t like being driven across UP, more so by a stranger. Juni picks up an aloo paratha to calm her nerves, Runi a ham sandwich.

Juni asks Alka if they can eat chips. At 6.40.

“Not right now, bohot early hai.” I tell her. “And why aren’t you talking to me?”

…

“No chips till 10.”

Second paratha for Juni. Tomato-cucumber sandwich for the other. We have snacks for days.1

I soon relent on the 10 o’clock chips timeline, advancing it to 7. Partly to win their hearts. Partly so I can eat chips. They play antakshari with Alka but if I try to help them out with a song, they stop. Juni stares out the window with a cold face and pretends not to know me. Runi thinks of something to say, looks at me and is reminded of my deed, then hmphs. She throws the occasional katti my way. I try to resolve this at the first bathroom break.

“Kya hua? This is because I shaved?”

Nodding heads.

“I’m still not looking like Papa?”

Shaking heads.

“Theek hai, now come on. You just have to get used to it.”

They do not. They continue their game of three-person antakshari, with Alka playing both sides. It is just after Moradabad that I stop on the side of the highway to draw on a moustache and stubble.

The next few hours are wonderful. Runi lets me join her team, we move on to I spy and count the cows, we eat more breakfast than necessary.

At the UP - Uttarakhand border toll, there is a long line of cars. The cops are conducting a routine check for booze. Apart from SUVs full of men who have started the party early, everyone drives through. Those free spirits are made to park on the side.

When it is our turn to pass, Inspector Rawat looks into the car at the four of us, and squints. In the back, he sees two dark-skinned six-year-olds who look exactly like each other but nothing like the fair-skinned Nepali lady sitting between them. In the front, he sees an empty passenger seat, and the driver: a bald man with shades, who looks nothing like the three people at the back. He barely makes eye contact with me, his attention drifting to other parts of my face. I am made to park on the side.

“Who are the girls?”

“My daughters.”

“Your daughters?” I understand his question.

“Yes... We adopted them a few years ago.”

“We means you and your wife?” He points to Alka. “She’s your wife?”

“No no, she’s their nanny” I clarify, a little embarrassed.

“Where is your wife?”

“England. She’s gone to meet her sister.”

“…”

“…”

“Where are you going?”

“Seetla. Near Mukteshwar. For summer vacation.”

He hesitates before asking his final question.

“What is on your face?”

I get out of the car and give him the highlights of the past twelve hours. The more I say, the more concerned he looks. He asks to see the adoption papers. Why would I carry them with me when we go on holiday so long after the adoption, I ask. Their Aadhar cards? School ID? Other ID?

“People usually don’t bother with children’s ID cards” I say with a smile. He raises an eyebrow.

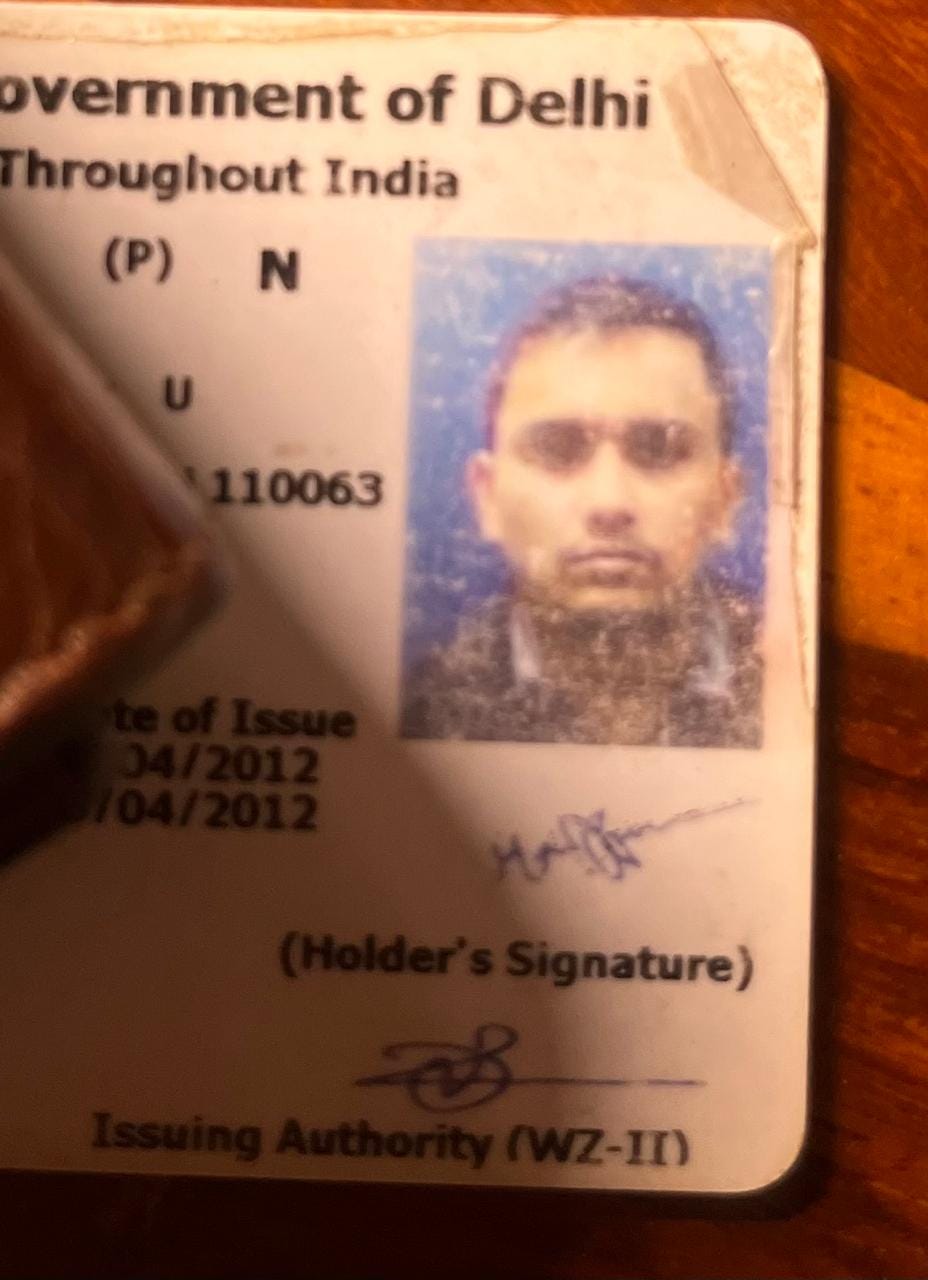

My Drivers’ License? I hand it over. Inspector Rawat looks at the faded photo of a man with a full head of hair, 12 years younger than the one in front of him. Surely, I must be carrying my own Aadhar card, he says. Surely! Unlike with the DL, the face on the Aadhar card is mine, and both cards have the same name, but the address does not match.

He wants to speak to their Mom. I call thrice. I don’t know why she won’t answer her fucking phone. Maybe because it is 5am on her first child-free Sunday in a year and she is sound asleep, secure in the knowledge that I will…well, manage.

“Sorry, why did you say you coloured your face?”

“I did it for the kids. They started crying when they saw me. They had never seen my face like this before. They said I didn’t look like Papa.”

“They said you did not look like their Papa?”

“Sir you are not understanding. They were hiding from me. They didn’t let me hold them or play any games. They were just not cooperating.”

He walks a few steps to talk with a junior cop, while I hang around to eavesdrop. I catch a few stray words. “… shak … kidnapping … paagal…”2

I beg him to speak with the kids.

Inspector Rawat sticks his pock-marked face into the rear window and releases a gush of paan breath. “BETA YE KAUN HAI?” he barks, hoping they will verify my identity. My tired, sweaty children have been sitting patiently in a stationary car in the middle of June, waiting for us to make a move. They cannot handle any more strangers. They look at the cop with tears filling their little eyes. Words do not reach their lips. I intervene. “Beta say PAPA.” Rawat Ji has had enough.

He calls out to the junior cop and asks him to accompany us to the local thana. “I am not arresting you. Just drive to the thana with the hawaldar and give your statement. And a copy of some ID for the children after you speak to their mother.” I drop names of the important people I know. I tell him my father spent twenty years as a doctor in the army and then worked at AIIMS and now he… But Rawat Ji does not take me seriously for some reason. He walks back to the check-point and I follow him desperately.

I faintly hear Alka call out to me from the car, but I’m just starting to change my approach with this man. Maybe there is some other way to sort this out. I ignore Alka once more, and then hear Juni scream “PAPA”.

We both turn. She has stuck her head out of the window and is looking unhappy.

“Juni wait,” I say, about to drop a hint.

But Rawat Ji is more interested to see that the child can speak. We walk to the car.

“Haan beta, bolo beta”, I reply, in my most loving tone, encouraging her to keep talking.

“Papa suno.”

“Beta bolo.”

“Idhar aa ke suno,” she says, calling me closer.

“Baby mai police uncle ka saath hoon na - aap bolo,” I explain that I cannot leave the cop’s side.

“PAPA PLEASE SUNO. Idhar.” The child is not messing around. She wants to have a private conversation. Now.

I lean in through the window. She puts one arm around me and cups my ear with her other hand. Then softly whispers, “Potty karna hai.” Thank god for poop.

Rawat Ji watches as Juni takes her arm off my neck and says “Chalo na” with the kind of impatience little girls reserve for their dads.

I explain the situation to him as discreetly as possible, so she does not know I have outed her. He takes a moment, then hands me my license. He reminds me to always carry at least a photocopy of their Aadhar cards. Oh Rawat Ji, never will I leave the house again without a dossier on every member of my family.

I get back in the car and turn on the AC. Juni cannot wait for us to leave. I catch Runi’s eye, and my own, when I adjust the rear-view mirror. Her look of panic from a short while ago has been replaced by good old disgust. The sweat has smudged away the black ink from my face. Runi hmphs again and a katti follows in the mirror. I raise my voice. “Okay enough Runi. Now stop it”. She starts to cry.

I look outside to spot Inspector Rawat. He has moved on to some college boys in a Scorpio. I open the dashboard and take out the black sketch pen.

“Papa chalooooo.” Juni says again.

“Just one second, jaan.”

A quick touch-up, and I put the car in first. Uttarakhand is fairly lax with checking. It’s unlikely we’ll be stopped again. And if we are, I guess we will just have to…well, manage.

PS: The photographs in this piece were taken to recreate the “look” recently, which is to say in the last one hour. The kids refused to be in the same room as me until I did the needful. Thankfully, this time Tara is not on holiday.

I did not expect to turn into the annoying women I grew up around - mother, grandmothers, aunts - but with our supplies, we could have survived a week in captivity and come out chubbier. Parathas, poha, three kinds of sandwiches, zeera cookies, coconut cookies, 50-50, fruit, and more chips than you will find at a poker tournament. I will spare you all our sources of hydration.

“… doubt … apharan … mad…”

The before-after photos are definitely papa-no papa photos. 🤩super.

Maanav, this is HILARIOUS! And so so well written!